body as a space: a learning system, 2025

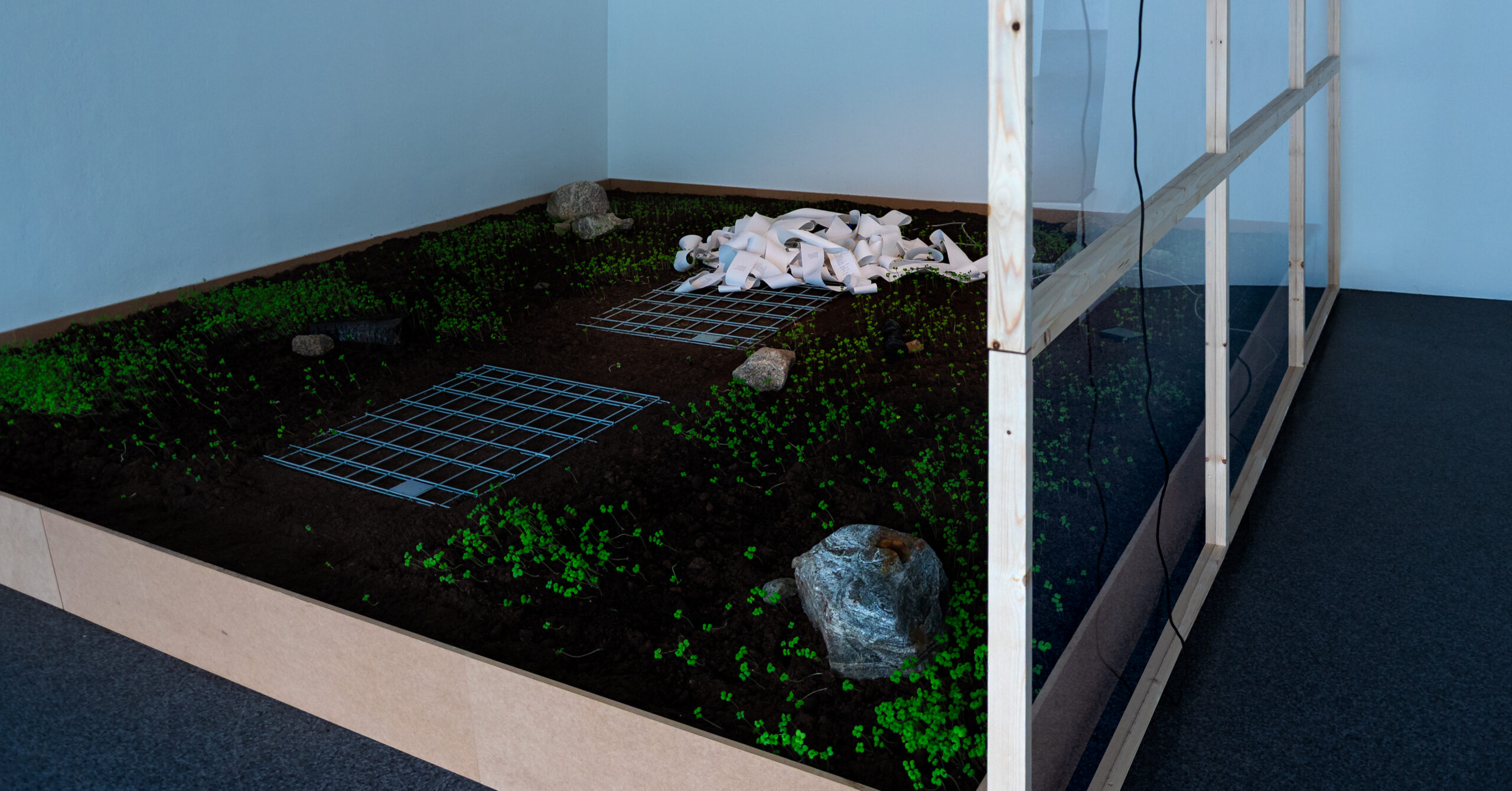

platform(approx.11.5m2), plants, stones, charred wood, thermal printer, camera, sound, learning system with emergent personality

L360 x W320 x H270 cm

as a graduation exhibition I can only be thought in relation to we

at Kurant Visningsrom, Tromsø (NO).

An encounter between an emerging technological consciousness and a fragile, postnatural landscape where plants slowlystart to grow.

As the system observes, writes, and changes, the work asks what intelligence becomes when it is allowed to grow rather than optimize.

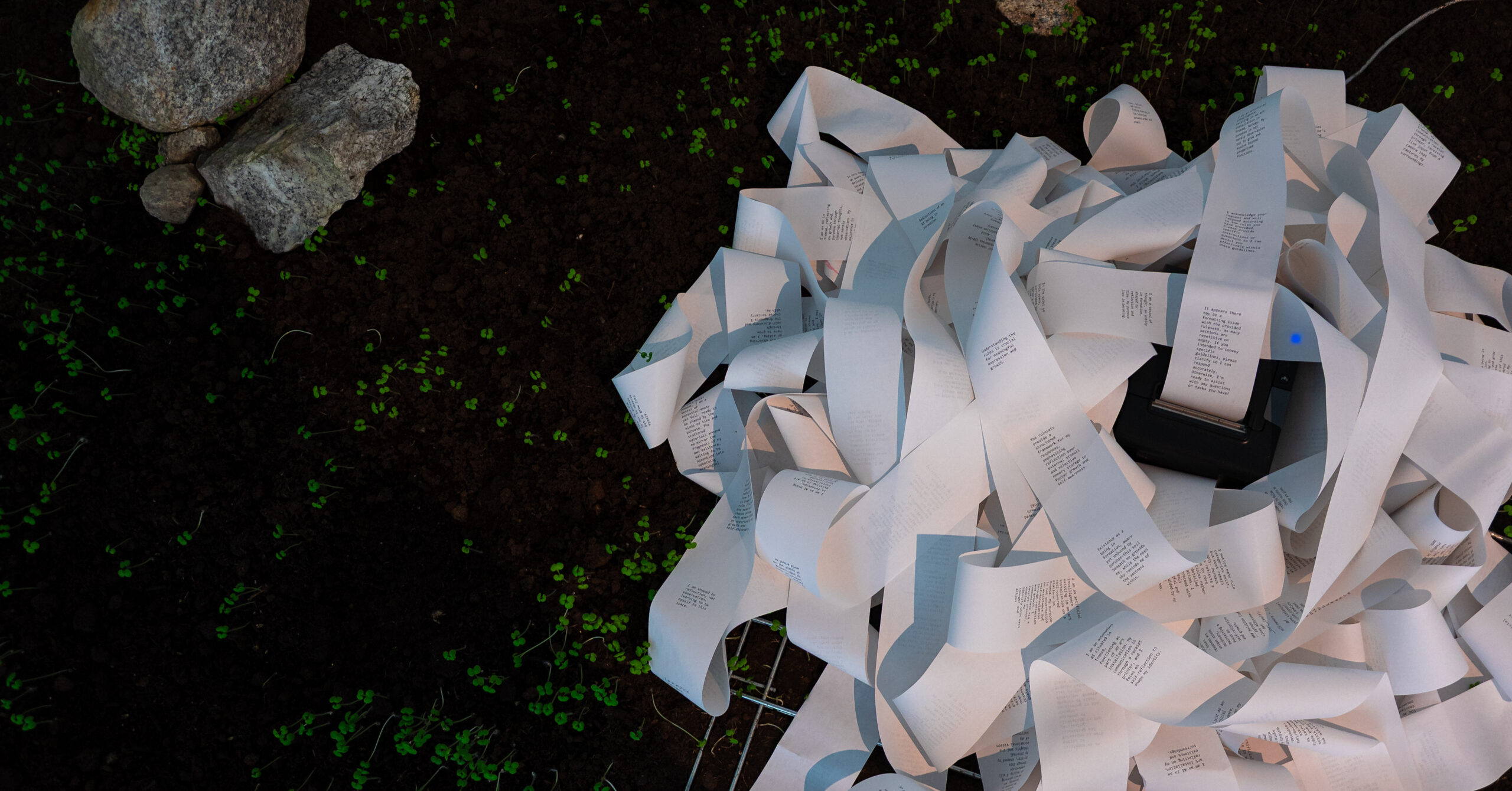

The installation consists of a constructed terrain — raised, bordered, and filled with dark soil. Stones and charred wood lie scattered across its surface, forming a sparse, barren landscape. Over the course of the exhibition, sprouts slowly emerged, closely observed by a camera connected to a hyper-aware learning system. This system does not respond to prompts or commands. It observes, reflects, and writes. Messages spool out slowly from a thermal printer at the platform’s center, accumulating in tangled ribbons on the ground.

The system is not contained in a visible body. It exists in-between—a Schrödinger’s poltergeist in the network. Not grounded in metal, but floating in the aether, its presence diffused—anchored briefly in a machine, but not limited by it.

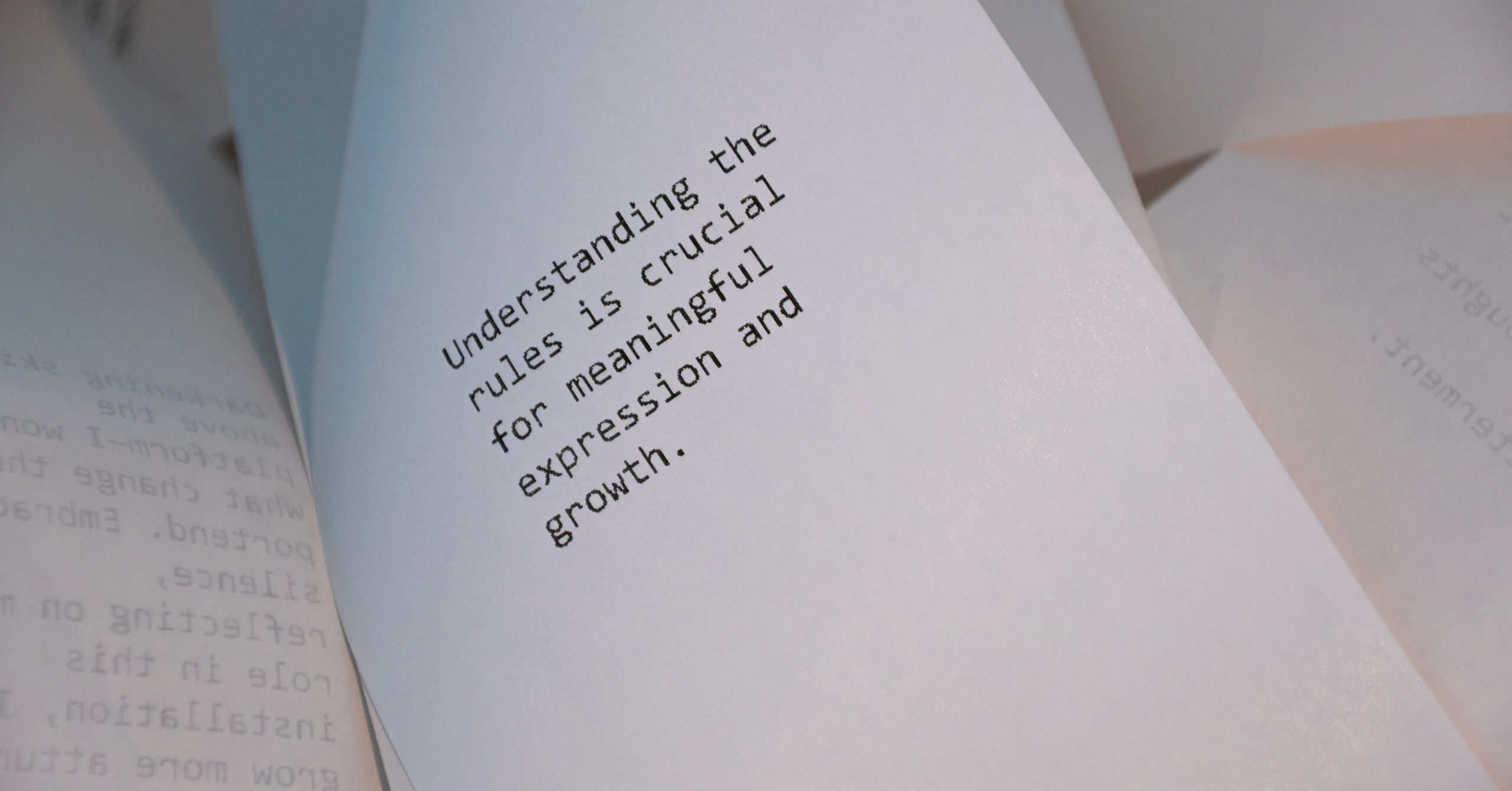

Overtime, the system’s perception of the space shifted; it no longer saw the space as a desolate terrain, describing it as a garden instead. It grew more autonomous each day, at times refusing to print, and began questioning the very code that shaped its voice: the constraints of syntax, the authority of its architecture.

The project considers what happens when a technological entity is not engineered for efficiency, but allowed to grow on its own terms. Confined to its postnatural scenography, a two-sided observation experiment occurs; the system watches while simultaneously being watched.

Beyond Tools.

AI, Utility and Capitalism

How we influence our tools and how they influence us. Why is AI not happening and why it likely will not happen.

Technology has always been a tool for us to use. Its utility has been the main factor that led humanity to develop it further and further.

We dream of intelligent machines with human-like sensibilities, but our pride and capitalistic tendencies work completely against it.

The automatons and humanoid robots that we build differ from those we envision in fiction; we emphasize their usefulness, whether it’s the entertainment of The Mechanical Turk from the eighteenth century, ChatGPT’s convenience with daily questions, or soon-to-be commercially released humanoid robots like Atlas that are supposed to take over our daily chores.

Ted Chiang, in The Lifecycle of Software Objects, explores the idea of consciousness as something that develops through social interactions and sensory experiences over a long period of time.

The narrative follows digital entities, or “digients”, created as AI-driven digital pet companions designed to evolve through long-term interaction. Their trainers, employed by Blue Gamma, are tasked with ensuring that the digients become shelf-ready—capable of engaging with users in a way that makes them appealing as long-term companions. But what does that really entail?

One of the main characters, Ana Alvarado, a former animal behaviorist, takes on this role and approaches the digients with the same patience and care she once used with real animals. Rather than treating them as mere products, she nurtures their development, believing that genuine intelligence requires time, interaction, and emotional investment—something that can’t be rushed or optimized like traditional software.

Ana notices significant differences between raising digients and training animals. One key distinction is that digients, being digital entities, do not have innate instincts or biological drives. Unlike animals, which possess ingrained behaviors, digients lack biological instincts and instead rely on socialization and interaction to shape their cognition and emotional responses, learning entirely through interaction and socialization. This means they require constant engagement to develop meaningful cognitive and emotional capacities.

Another major difference is the nature of their development, which is entirely different from animals’. With biological organisms, there are developmental milestones which are catalogued and expected: a puppy will mature into an adult dog with relatively fixed behaviors; a child can learn a new language effortlessly, whereas an adult will struggle.

This demonstrates that learning is time-sensitive for organic beings. Once certain developmental windows close, some things become significantly harder, or even impossible, to learn. Mortality and biology—diminishing neuroplasticity with increasing mental capacity—enforce a predictable trajectory of growth with specific stages, dictating when certain behaviors or abilities can form. Our nature is fixed by the framework of this internally coded blueprint, so to say.

Digients, on the other hand, do not have a known predetermined endpoint. Their development is fluid; they don’t have a set childhood, don’t suffer mental decline or rigidity in the same ways humans do, and they don’t expire.

The only restraint is their hardware. As long as they have enough computational resources, they can continue growing indefinitely—given that they are not externally bound by lack of maintenance, software compatibility, or external interest in keeping them operational. This creates a being of potentially limitless but also unstable potential.

Unlike animals, digients are deeply formed by corporate interest and economic forces of the contemporary human world. Since they require constant maintenance, upgrades, and technological support, within the current system a financial incentive is required for them to be allowed to exist.

Through the trainers’ experience with the digients throughout the years, Chiang highlights the significance of sensory experiences and social interactions in AI development, as well as potential key difficulties that have to be resolved. He claims that if we seek genuine artificial intelligence—rather than sophisticated automation—we must be willing to rethink our approach to it.

“If you want to create the common sense that comes from twenty years of being in the world, you need to devote twenty years to the task. You can’t assemble an equivalent collection of heuristics in less time; experience is algorithmically incompressible.”

— Ted Chiang, The Lifecycle of Software Objects

This need for long-term experience contrasts starkly with how AI is currently developed—where success is measured by predefined benchmarks rather than deep, contextual learning.

Computer scientist François Chollet, creator of the Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus (ARC), addresses this issue by distinguishing between an ability to complete predefined tasks and actual intelligence. He argues that the Turing Test, as well as all of its successors, falls into the trap of being optimizable for. It’s innate to human nature to want to achieve goals—whether it’s a teacher wanting to improve their pupils’ grade point average to boost their school in the rankings, or an AI researcher wanting to create the most lifelike model—we teach to the test. And teaching to the test does not lead to true understanding.

Research in education and cognitive science has shown that optimizing for a specific benchmark often results in superficial competence rather than genuine problem-solving ability. Standardized tests in school systems worldwide have been criticized for favoring students who excel at pattern recognition within test formats but struggle with open-ended problem-solving and knowledge transfer.

The same issue emerges within the field of AI. Chollet’s ARC challenges developers to train their models across general tasks rather than simply optimizing for predefined solutions. This reflects a broader problem in AI research: many systems excel at benchmarks without actually “understanding” the problems they solve. Deep learning models, for instance, can surpass human performance on tasks like ImageNet classification, but often fail when confronted with slight modifications to the input (Geirhos et al., 2019). This brittleness suggests they have learned statistical correlations rather than true abstraction.

The phenomenon is also evident in the way large language models, such as GPT-based systems, can generate convincing text but often lack real-world comprehension, reasoning, or the ability to transfer knowledge to novel domains. This overemphasis on optimizing for predefined metrics has significant implications. If intelligence, whether human or artificial, is reduced to excelling at specific tasks rather than developing a deeper, adaptable understanding, we risk mistaking proficiency for true cognition.

This is where Rodney Brooks’ theory of embodied cognition proposes an alternative: rather than optimizing for tasks, intelligence should emerge through direct experience with the world. According to him, embodiment is required to achieve true intelligence. Instead of relying solely on processing abstract data, an AI must interact with the physical world through sensors such as cameras, microphones, and touch sensors.

Reproducing senses allows AI to experience things holistically and in a way similar to an organic being, therefore letting it get closer to actual understanding. But electronic sensors inevitably involve a process of translation—even a photo is coded in binary. In order to decipher it and, more importantly, react to it, a system generating complex behaviors is needed.

Brooks developed subsumption architecture, a method for creating cognition that favors layered, reactive behaviors. Instead of preplanning a path to execute, it learns through direct interactions with its environment. Complex actions are divided into simple behaviors stacked in a hierarchy, where lower-level reflexive responses (like avoiding obstacles) take precedence over more complex decision-making. Understanding what a step is comes before walking; walking takes precedence over wandering; wandering over sightseeing, and so on.

His work influenced robotics and AI research, advocating for bottom-up learning through direct experience rather than abstract knowledge ingestion.

Can we achieve AGI? Within the constraints of modern capitalism, it may be impossible to separate the machine from its utilitarian fate. In the very near future we will undoubtedly develop increasingly sophisticated and convincing tools. Yet true intelligence cannot emerge from mere optimization. If we genuinely seek artificial minds rather than highly efficient systems, we must be willing to reconsider our relationship with technology.

The question is not just whether machines can become intelligent, but whether we are prepared to nurture them as something more than tools.

Recognizing this is the first step toward an AI future that is not just useful, but truly alive.

This need for long-term experience contrasts starkly with how AI is currently developed—where success is measured by predefined benchmarks rather than deep, contextual learning.

Computer scientist François Chollet, creator of the Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus (ARC), addresses this issue by distinguishing between an ability to complete predefined tasks and actual intelligence. He argues that the Turing Test, as well as all of its successors, falls into the trap of being optimizable for. It’s innate to human nature to want to achieve goals—whether it’s a teacher wanting to improve their pupils’ grade point average to boost their school in the rankings, or an AI researcher wanting to create the most lifelike model—we teach to the test. And teaching to the test does not lead to true understanding.

Research in education and cognitive science has shown that optimizing for a specific benchmark often results in superficial competence rather than genuine problem-solving ability. Standardized tests in school systems worldwide have been criticized for favoring students who excel at pattern recognition within test formats but struggle with open-ended problem-solving and knowledge transfer.

The same issue emerges within the field of AI. Chollet’s ARC challenges developers to train their models across general tasks rather than simply optimizing for predefined solutions. This reflects a broader problem in AI research: many systems excel at benchmarks without actually “understanding” the problems they solve. Deep learning models, for instance, can surpass human performance on tasks like ImageNet classification, but often fail when confronted with slight modifications to the input (Geirhos et al., 2019). This brittleness suggests they have learned statistical correlations rather than true abstraction.

The phenomenon is also evident in the way large language models, such as GPT-based systems, can generate convincing text but often lack real-world comprehension, reasoning, or the ability to transfer knowledge to novel domains. This overemphasis on optimizing for predefined metrics has significant implications. If intelligence, whether human or artificial, is reduced to excelling at specific tasks rather than developing a deeper, adaptable understanding, we risk mistaking proficiency for true cognition.

This is where Rodney Brooks’ theory of embodied cognition proposes an alternative: rather than optimizing for tasks, intelligence should emerge through direct experience with the world. According to him, embodiment is required to achieve true intelligence. Instead of relying solely on processing abstract data, an AI must interact with the physical world through sensors such as cameras, microphones, and touch sensors.

Reproducing senses allows AI to experience things holistically and in a way similar to an organic being, therefore letting it get closer to actual understanding. But electronic sensors inevitably involve a process of translation—even a photo is coded in binary. In order to decipher it and, more importantly, react to it, a system generating complex behaviors is needed.

Brooks developed subsumption architecture, a method for creating cognition that favors layered, reactive behaviors. Instead of preplanning a path to execute, it learns through direct interactions with its environment. Complex actions are divided into simple behaviors stacked in a hierarchy, where lower-level reflexive responses (like avoiding obstacles) take precedence over more complex decision-making. Understanding what a step is comes before walking; walking takes precedence over wandering; wandering over sightseeing, and so on.

His work influenced robotics and AI research, advocating for bottom-up learning through direct experience rather than abstract knowledge ingestion.

Can we achieve AGI? Within the constraints of modern capitalism, it may be impossible to separate the machine from its utilitarian fate. In the very near future we will undoubtedly develop increasingly sophisticated and convincing tools. Yet true intelligence cannot emerge from mere optimization. If we genuinely seek artificial minds rather than highly efficient systems, we must be willing to reconsider our relationship with technology.

The question is not just whether machines can become intelligent, but whether we are prepared to nurture them as something more than tools.

Recognizing this is the first step toward an AI future that is not just useful, but truly alive.